#baltimore uprising

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

2015 photo in Baltimore by Devin Allen

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Empire: Uprising TPB signed by Barry Kitson at the 2024 Baltimore ComicCon

#empire: uprising#empire#barry kitson#idw comics#00s comics#autographed comics#signed comics#baltimore comic con#Baltimore ComicCon

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

what is the 1033 program?

The U.S. Department of Defense administers the 1033 program, which transfers excess military equipment to U.S. police forces—federal, state and local. This program has so far sent $6 billion in military gear to police departments. The militarized police responses seen in Ferguson in 2014, Baltimore in 2015 and in cities throughout the country during the 2020 uprisings after George Floyd’s murder can be directly attributed to the 1033 program.

The demand to abolish the 1033 program has been a part of the Black Alliance for Peace (BAP)’s program since its founding. Read more about our program and our umbrella campaign, No Compromise, No Retreat: Defeat the War on African/Black People in the U.S. and Around the World.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Haitian Immigration : Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

Many Haitians moved to Louisiana during and after the Haitian Revolution, which began in 1791 and lasted for 13 years:

The long, interwoven history of Haiti and the United States began on the last day of 1698, when French explorer Sieur d'Iberville set out from the island of Saint Domingue (present-day Haiti) to establish a settlement at Biloxi, on the Gulf Coast of France's Louisiana possession.

For most of the eighteenth century, however, only a few African migrants settled there. But between the 1790s and 1809, large numbers of Haitians of African descent migrated to Louisiana. By 1791 the Haitian Revolution was under way. It would continue for thirteen years, result in the independence of the first African republic in the Western Hemisphere, and reverberate throughout the Atlantic world. Its impact would be particularly felt in Louisiana, the destination of thousands of refugees from the island's turmoil. Their activism had profound repercussions on the politics, the culture, the religion, and the racial climate of the state.

From Saint Domingue to Louisiana

Louisiana and her Caribbean parent colony developed intimate links during the eighteenth century, centered on maritime trade, the exchange of capital and information, and the migration of colonists. From such beginnings, Haitians exerted a profound influence on Louisiana's politics, people, religion, and culture. The colony's officials, responding to anti-slavery plots and uprisings on the island, banned the entry of enslaved Saint Domingans in 1763. Their rebellious actions would continue to impact upon Louisiana's slave trade and immigration policies throughout the age of the American and French revolutions.

These two democratic struggles struck fear in the hearts of the Spaniards, who governed Louisiana from 1763 to 1800. They suppressed what they saw as seditious activities and banned subversive materials in a futile attempt to isolate their colony from the spread of democratic revolution. In May 1790 a royal decree prohibited the entry of blacks - enslaved and free - from the French West Indies. A year later, the Haitian Revolution started.

The revolution in Saint Domingue unleashed a massive multiracial exodus: the French fled with the bondspeople they managed to keep; so did numerous free people of color, some of whom were slaveholders themselves. In addition, in 1793, a catastrophic fire destroyed two-thirds of the principal city, Cap Français (present-day Cap Haïtien), and nearly ten thousand people left the island for good. In the ensuing decades of revolution, foreign invasion, and civil war, thousands more fled the turmoil. Many moved eastward to Santo Domingo (present-day Dominican Republic) or to nearby Caribbean islands. Large numbers of immigrants, black and white, found shelter in North America, notably in New York, Baltimore (fifty-three ships landed there in July 1793), Philadelphia, Norfolk, Charleston, and Savannah, as well as in Spanish Florida. Nowhere on the continent, however, did the refugee movement exert as profound an influence as in southern Louisiana.

Between 1791 and 1803, thirteen hundred refugees arrived in New Orleans. The authorities were concerned that some had come with "seditious" ideas. In the spring of 1795, Pointe Coupée was the scene of an attempted insurrection during which planters' homes were burned down. Following the incident, a free émigré from Saint Domingue, Louis Benoit, accused of being "very imbued with the revolutionary maxims which have devastated the said colony" was banished. The failed uprising caused planter Joseph Pontalba to take "heed of the dreadful calamities of Saint Domingue, and of the germ of revolt only too widespread among our slaves." Continued unrest in Pointe Coupée and on the German Coast contributed to a decision to shut down the entire slave trade in the spring of 1796.

In 1800 Louisiana officials debated reopening it, but they agreed that Saint Domingue blacks would be barred from entry. They also noted the presence of black and white insurgents from the French West Indies who were "propagating dangerous doctrines among our Negroes." Their slaves seemed more "insolent," "ungovernable," and "insubordinate" than they had just five years before.

That same year, Spain ceded Louisiana back to France, and planters continued to live in fear of revolts. After future emperor Napoleon Bonaparte sold the colony to the United States in 1803 because his disastrous expedition against Saint Domingue had stretched his finances and military too thin, events in the island loomed even larger in Louisiana.

The Black Republic and Louisiana

In January 1804, an event of enormous importance shook the world of the enslaved and their owners. The black revolutionaries, who had been fighting for a dozen years, crushed Napoleon's 60,000 men-army - which counted mercenaries from all over Europe - and proclaimed the nation of Haiti (the original Indian name of the island), the second independent nation in the Western Hemisphere and the world's first black-led republic. The impact of this victory of unarmed slaves against their oppressors was felt throughout the slave societies. In Louisiana, it sparked a confrontation at Bayou La Fourche. According to white residents, twelve Haitians from a passing vessel threatened them "with many insulting and menacing expressions" and "spoke of eating human flesh and in general demonstrated great Savageness of character, boasting of what they had seen and done in the horrors of St. Domingo [Saint Domingue]."

The slaveholders' anxieties increased and inspired a new series of statutes to isolate Louisiana from the spread of revolution. The ban on West Indian bondspeople continued and in June 1806 the territorial legislature barred the entry from the French Caribbean of free black males over the age of fourteen. A year later, the prohibition was extended: all free black adult males were excluded, regardless of their nationality. Severe punishments, including enslavement, accompanied the new laws.

However, American efforts to prevent the entry of Haitian immigrants proved even less successful than those of the French and the Spanish. Indeed, the number of immigrants skyrocketed between May 1809 and June 1810, when Spanish authorities expelled thousands of Haitians from Cuba, where they had taken refuge several years earlier. In the wake of this action, New Orleans' Creole whites overcame their chronic fears and clamored for the entry of the white refugees and their slaves. Their objective was to strengthen Louisiana's declining French-speaking community and offset Anglo-American influence. The white Creoles felt that the increasing American presence posed a greater threat to their interests than a potentially dangerous class of enslaved West Indians.

American officials bowed to their pressure and reluctantly allowed white émigrés to enter the city with their slaves. At the same time, however, they attempted to halt the migration of free black refugees. Louisiana's territorial governor, William C. C. Claiborne, firmly enforced the ban on free black males. He advised the American consul in Santiago de Cuba:

Males above the age of fifteen, have . . . been ordered to depart. - I must request you, Sir, to make known this circumstance and also to discourage free people of colour of every description from emigrating to the Territory of Orleans; We have already a much greater proportion of that population than comports with the general Interest.

Claiborne and other officials labored in vain; the population of Afro-Creoles grew larger and even more assertive after the entry of the Haitian émigrés from Cuba, nearly 90 percent of whom settled in New Orleans. The 1809 migration brought 2,731 whites, 3,102 free persons of African descent, and 3,226 enslaved refugees to the city, doubling its population. Sixty-three percent of Crescent City inhabitants were now black. Among the nation's major cities only Charleston, with a 53 percent black majority, was comparable.

The multiracial refugee population settled in the French Quarter and the neighboring Faubourg Marigny district, and revitalized Creole culture and institutions. New Orleans acquired a reputation as the nation's "Creole Capital."

The rapid growth of the city's population of free persons of color strengthened the "three-caste" society - white, mixed, black - that had developed during the years of French and Spanish rule. This was quite different from the racial order prevailing in the rest of the United States, where attempts were made to confine all persons of African descent to a separate and inferior racial caste - a situation brought about by political reality in the South that promoted white unity across class lines and the immersion of all blacks into a single and subservient social caste.

In Louisiana, as lawmakers moved to suppress manumission and undermine the free black presence, the refugees dealt a serious blow to their efforts. In 1810 the city's French-speaking Creoles of African descent, reinforced by thousands of Haitian refugees, formed the basis for the emergence of one of the most advanced black communities in North America.

Soldiers, Rebels, and Pirates

Many Haitian black males eluded immigration authorities by slipping into the territory through Barataria, a coastal settlement just west of the Mississippi River. Some became allies of the notorious pirates Jean and Pierre Lafitte, white refugees of the Haitian Revolution. Surrounded by marshland and a maze of waterways, Barataria was an effective staging area for attacks on Gulf shipping. The interracial band of adventurers dominated the settlement's thriving black-market economy.

But pirates and smugglers did not make up the whole of Barataria's fugitive residents. Some two hundred free black veterans of the Haitian Revolution, including Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Savary, a former French republican officer, were among them. In 1799 seven hundred soldiers, opposed to Toussaint L'Ouverture fled to Cuba and later migrated to Louisiana. By 1810 this movement of Haitian soldiers from Cuba had created a black military presence in Louisiana that seriously worried Governor Claiborne. He anxiously requested reinforcements. The number of free black men "in and near New Orleans, capable of carrying arms," he wrote, "cannot be less than eight hundred."

Colonel Savary and other republican veterans of the Haitian Revolution remained committed to the French revolution's ideals of liberté, egalité, fraternité (freedom, equality, fraternity.) They regrouped to aid insurgents attempting to establish independent republics in Latin America. In November 1813 Savary offered to send five hundred Haitian soldiers to fight with Mexican revolutionaries. When their effort to establish a Mexican government in Texas failed, Savary and his men returned to New Orleans. Within the year, however, the colonel and other Haitian veterans would be rallying against the forces of the British crown.

As British forces threatened to invade New Orleans in 1814, American authorities sought to win the loyalty of battle-hardened black soldiers like Colonel Savary. They were also well aware of the prominent role that free men had played in slave rebellions. With the English approaching, pacifying them would be strategically sound.

General Andrew Jackson arrived in New Orleans in December 1814 and immediately mustered 350 native-born black veterans of the Spanish militia into the United States Army. Colonel Savary raised a second black unit of 250 of Haiti's refugee soldiers. Jackson recognized Savary's considerable influence and knew of his reputation as "a man of great courage." On Jackson's orders, Savary became the first African-American soldier to achieve the rank of second major.

The Haitians in Barataria also fought in the battle of New Orleans. In September 1814 federal troops invaded their community and dispersed the Lafittes and their followers. Hundreds of refugees poured into the city. Andrew Jackson offered them pardons in return for their support in defending the city. After the victory, he commended the two battalions of six hundred African-American and Haitian soldiers whose presence in a force of three thousand men had proved decisive. He praised the "privateers and gentlemen" of Barataria who "through their loyalty and courage, redeemed [their] pledge . . . to defend the country."

Jackson observed that Captain Savary "continued to merit the highest praise." In the last significant skirmish of the battle, Savary and a detachment of his men volunteered to clear the field of a detail of British sharpshooters. Though Savary's force suffered heavy casualties, the mission was carried out successfully.

Within weeks of the victory, however, Jackson yielded to white pressure to remove the men from New Orleans to a remote site in the marshland east of the city to repair fortifications. Savary relayed a message to the general that his men "would always be willing to sacrifice their lives in defense of their country as had been demonstrated but preferred death to the performance of the work of laborers." Jackson, though not pleased, refrained from taking any action against the troops. In February, the general even lent his support to Savary's renewed efforts to rejoin republican insurgents in Mexico.

Afro-Creoles and Americans

In colonial Louisiana and in colonial Haiti, military service had functioned as a crucial means of advancement for both free and enslaved blacks. After the battle of New Orleans, however, support for the black militia declined among free people of color. The disrespect shown to the soldiers who fought so valiantly, along with their disappointment at not receiving some measure of political recognition, contributed to their disillusionment.

Afro-Creoles' anger mounted as Louisiana's white lawmakers embarked upon an unprecedented and sustained attack upon their rights by formulating one of the harshest slave codes in the American South. In 1830 the legislature reaffirmed the 1807 ban on the entry of "free negroes and mulattoes" and required slaveholders to ensure the removal of freed people within thirty days of their emancipation. In Louisiana, as elsewhere in the South, segregation, anti-miscegenation laws, and the legal ostracism of racially mixed children signified the imposition of a two-category pattern of racial classification that relegated all persons of African ancestry to a degraded status.

Reduced to a debased condition, deprived of citizenship, denied free movement, and threatened with violence, Afro-Creoles, both native-born and immigrant, developed an intensely antagonistic relationship with the new regime. Under the United States government, black Louisianians had anticipated an end to slavery and racial oppression and had looked for the fulfillment of the democratic ideals embodied in the founding principles of the new American republic. But contrary to their expectations, the process of Americanization negated the promise of the revolutionary era. Instead of moving toward freedom and equality, the new government promoted the evolution of an increasingly harsh system of chattel slavery.

From Revolution to Romanticism

Following the example of intellectuals in France and Haiti, Afro-Creole activists in Louisiana - led by Haitian émigrés, their children, and French-speaking native Louisianians - had been nurturing their republican heritage. As political expression was stifled, they poured their energies into a new vehicle of revolutionary ideas, the Romantic literary movement.

New Orleans' highly politicized black intelligentsia thereby tapped into the Atlantic world's ongoing current of political radicalism, protesting injustice in their literary work. Their principal forum was La Société des Artisans. Founded by free black artisans and veterans of the War of 1812, the organization provided local Creole writers the opportunity to exchange ideas and present their numerous artistic works in a friendly setting.

Among these young writers was Victor Séjour. His father, a Haitian émigré, was a veteran of the War of 1812 and a prosperous dry-goods merchant. The young Séjour had been educated at New Orleans' prestigious black school Académie Sainte-Barbe, under the tutelage of Michel Séligny, the most productive Afro-Creole short-story writer. Séjour's audience at La Société proclaimed him a prodigy, and his father, determined to see his son fulfill his artistic potential and anxious for Victor to escape the burden of racial prejudice in Louisiana, sent him to France to complete his education. In Paris, the youth quickly came under the influence of another writer of African-Haitian descent, renowned novelist Alexandre Dumas, author of The Three Musketeers (1844), The Count of Monte Cristo (1844-45), and many other celebrated works.

Séjour made a dramatic debut on the literary scene with the publication, in March 1837, of an impassioned attack on slavery, "Le Mulâtre" (The Mulatto), the first short story by an African-American writer to be published in France.

Following the publication of "Le Mulâtre," Séjour embarked on a remarkably productive artistic career. When he was only twenty-six years old, the famed Théâtre Français produced his first drama; it would be followed by two dozen more. In one season, French theaters produced three of his works simultaneously, and Emperor Napoleon III attended opening nights of two of them.

Ironically, Séjour's first story, though it may have circulated privately within the black community, was never published in New Orleans. It fell within the parameters of an 1830 Louisiana law prohibiting reading matter "having a tendency to produce discontent among the free coloured population . . . or to excite insubordination among the slaves." Violators faced either a penalty of three to twenty-one years at hard labor or death, at the judge's discretion.

Despite such restrictions, the city's free people of color managed to fashion a vibrant literary movement, dominated by Haitian refugees and their descendants. The influence of the French Romantic movement among New Orleans' black intellectuals became more evident in 1843 with the publication of a short-lived, interracial literary journal L'Album littéraire: Journal des jeunes gens, amateurs de littérature (The Literary Album: A Journal of Young Men, Lovers of Literature). Its most prominent black founder was Armand Lanusse, of Haitian ancestry and one of the city's leading Romantic artists. Lanusse and his fellow writers, both émigré and native-born, ignored the 1830 literary censorship law and, like their fellow Romantics in France and Haiti, used their literary skills to challenge existing social evils.

In a series of introductory essays,the anonymous contributors to L'Album deplored "the sad and awful condition of Louisiana society," where the spectacle of rampant greed, unrelieved poverty, and institutionalized injustice "grips our hearts with deep sorrow, showering grief over all our thoughts, filling the soul with terror and despair."

Within a year of its debut, L'Album disappeared from the literary scene after critics attacked the journal for advocating revolt. Lanusse then edited a collection of poems by Creoles of color in 1845; Les Cenelles: Choix de poésies indigènes was the first anthology of literature by African Americans in the United States. Les Cenelles was much more subdued in tone than its predecessor. Still, Lanusse in his preface emphasized the value of education as "a shield against the spiteful and calamitous arrows shot at us." He and his colleagues considered their art form a springboard to social and political reform.

The Haitian Influence on Religion

In 1847 Lanusse and his friends helped to assure the survival of a small Catholic religious order dedicated to charitable work among the city's enslaved people and free black indigents. The congregation of the Sisters of the Holy Family was founded in 1842 by Henriette Delille, yet another prominent Afro-Creole of Haitian ancestry. As Delille's sisterhood struggled to maintain their community during the 1840s, a coalition of Afro-Creole writers, artisans, and philanthropists obtained corporate status and funding for the religious society.

When Delille took her formal religious vows in 1852, she headed Louisiana's first Catholic religious order of black women and the nation's second African-American community of Catholic nuns. Bearing striking testimony to the enormous impact of the Haitian diaspora, the first Catholic community of African-American nuns, the Oblate Sisters of Providence, founded in 1829 in Baltimore, originated in the Haitian refugee movement.

In 1848, Armand Lanusse and other Romantic writers took concrete measures to promote reform by establishing La Société Catholique pour l'Instruction des Orphelins dans l'Indigence (Catholic Society for the Instruction of Indigent Orphans). Through their organization, black activists executed the terms of a bequest by Madame Justine Firmin Couvent, a native of Guinea and a former slave, to establish a school in the Faubourg Marigny for the district's destitute orphans of color. Appalled by the indigence and illiteracy of the children, Couvent donated land and several buildings for an educational facility of which Lanusse became the first principal.

While Lanusse pursued his reform agenda within the existing institutional framework, another contributor to the volume, Nelson Desbrosses, followed a nontraditional path to empowerment and change. He traveled to Haiti before the Civil War, studied with a leading practitioner of Vodou, and returned to New Orleans with a reputation as a successful healer and spirit medium. Desbrosses undoubtedly recognized Vodou's historical significance in Haiti's independence struggle. During the revolution, the religion served as a medium for political organization as well as an ideological force for change. On the battlefield, Vodou's spiritual power proved decisive in reinforcing the determination of revolutionaries in their struggle for freedom. In the North Province, houngans (Vodou priests) sustained the revolt by mobilizing as many as forty thousand enslaved people.

Vodou thrived in New Orleans until the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, when President Thomas Jefferson and other political leaders sought to undermine Creole predominance by Americanizing the culture of southern Louisiana. The post-1809 influx of Haitian refugees, however, slowed the Americanization process and assured the vitality of New Orleans' Creole culture for another twenty-five years. Immigrant believers in Vodou infused the religion's Louisiana variant with Afro-Caribbean elements of belief and ritual.

In the relatively tolerant religious milieu of antebellum New Orleans, Haitian immigrants joined with Creole slaves, free blacks, and even whites to assure the religion's ascendancy. Through Vodou, practiced in secrecy, Afro-Creoles preserved the memory of their African past and experienced psychological release by way of a religion that served as one of the few areas of totally autonomous black activity.

In transcending ethnic, class, and gender distinctions, Vodou helped to sustain a liberal Latin European religious ethic that recognized the spiritual equality of all persons. Vodou's interracial appeal and egalitarian spirit, reinvigorated by Haitian immigrants, offered a dramatic alternative to the Anglo-American racial order.

Beginning in the 1860s, Vodou assemblies were systematically suppressed, but the famed "Vodou Queen" Marie Laveau continued to exert great influence over her interracial following. In 1874 some twelve thousand spectators swarmed to the shores of Lake Pontchartrain to catch a glimpse of Laveau performing her legendary rites. By that time Laveau and other Afro-Creole Vodouists had fashioned some of the nation's most lasting folkloric traditions, as well as a religion of resistance that endures to the present moment.

The Civil War

Federal forces occupied New Orleans in 1862, and black Creoles volunteered their services to the Union army. The newspaper L'Union - whose chief founders, Dr. Louis Charles Roudanez and his brother, Jean-Baptiste, were of Haitian ancestry - announced its agenda in the premier issue. The editors condemned slavery, blasted the Confederacy, and expressed solidarity with Haiti's revolutionary republicans.

An 1862 editorial written by a newly enlisted Union officer, Afro-Creole Romantic writer Henry Louis Rey, urged free men of color to join the U.S. Army and take up "the cause of the rights of man." Rey invoked the names of Jean-Baptiste Chavannes and Vincent Ogé. Their ill-fated 1790 revolt had paved the way for the Haitian Revolution:

CHAVANNE [sic] and OGÉ did not wait to be aroused and to be made ashamed; they hurried unto death; they became martyrs here on earth and received on high the reward due to generous hearts...hasten all; our blood only is demanded; who will hesitate?

The editors of L'Union described Rey and the Afro-Creole troops as the "worthy grandsons of the noble [Col. Joseph] Savary." The paper insisted that military service entitled them to the political equality that had been denied their ancestors who fought valiantly in the American Revolution and the War of 1812. Furthermore, its editors warned, the men had resolved to "protest against all politics which would tend to expatriate them."

When federal officials undermined their suffrage campaign, Afro-Creole leaders took their case to the highest level. In 1864 L'Union cofounder Jean-Baptiste Roudanez and E. Arnold Bertonneau, a former officer in the Union army, met with President Abraham Lincoln; they urged him to extend voting rights to all Louisianians of African descent.

In L'Union, and its successor, La Tribune, the Roudanez brothers and their allies foresaw the complete assimilation of African Americans into the nation's political and social life. During Reconstruction they called on the federal government to divide confiscated plantations into ten-acre plots, to be distributed to displaced black families. They insisted that the formely enslaved were "entitled by a paramount right to the possession of the soil they have so long cultivated."

The aggressive stance and republican idealism of La Tribune prompted the authors of Louisiana's 1868 state constitution to envision a social and political revolution. The new charter required state officials to swear that they recognized the civil and political equality of all men. Alone among Reconstruction constitutions, Louisiana explicitly required equal access to public accommodations and forbade segregation in public schools.

The Consequences of the Haitian Migration

After Reconstruction collapsed in 1877, Creole activists fought the restoration of white rule. In 1890 Rodolphe L. Desdunes, a Creole New Orleanian of Haitian descent, joined with other prominent rights advocates to challenge state-imposed segregation. Their legal battle culminated in the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision. Though the nation's highest tribunal upheld the "separate but equal" doctrine, the decision included a powerful dissent that would be used to rescue the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments in later Supreme Court decisions. The descendants of Haitian immigrants would play key roles in civil rights campaigns of the twentieth century.

Haitians exerted an enormous influence on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Louisiana. Their sustained resistance to Saint Domingue's regime of bondage forced repeated changes in French, Spanish, and American immigration policies as frightened white officials attempted to isolate Louisiana from the spread of black revolt.

The massive 1809 influx of Haitian refugees ensured the survival of a wealth of West African cultural transmissions, as well as a Latin European racial order that enhanced the social and economic mobility of both free and enslaved blacks. In early-nineteenth-century New Orleans, the immigrants and their descendants infused the city's music, cuisine, religious life, speech patterns, and architecture with their own cultural traditions. Reminders of their Creole influence abound in the French Quarter, the Faubourg Marigny, the Faubourg Tremé, and other city neighborhoods.

The refugee population also reinforced a brand of revolutionary republicanism that impacted American race relations for decades. With an unflagging commitment to the democratic ideals of the revolutionary era, Haitian immigrants and their descendants appeared at the head of virtually every New Orleans civil rights campaign. Their leadership role in the struggle for racial justice offers dramatic evidence of the scope of their influence on Louisiana's history. From Colonel Joseph Savary's militant republicanism to Rodolphe Desdunes's unrelenting attacks on state-enforced segregation, Haitian émigrés and their descendants demanded that the nation fulfill the promise of its founding principles.

In his 1911 book Our People and Our History, Rodolphe Desdunes described Armand Lanusse's anthology, Les Cenelles, as a "triumph of the human spirit over the forces of obscurantism in Louisiana that denied the education and intellectual advancement of the colored masses." African Americans in Louisiana triumphed over these forces in their distinguished history of military service, their embrace of artistic and scholarly pursuits, their campaign for humanitarian reforms, and their Civil War vision of a reconstructed nation of racial equality. Their Haitian heritage was central to those victories.

#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#brownskin#brown skin#afrakans#haitian#haiti#vodun#voodoo#voodou#afrakan spirituality#african culture#haitian heritage#louisiana#migration#migrant#migrants

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's the most intense mission you've ever been on?

The most intense mission I've ever been on? Well, it'd definitely have to be the Twotanic case...but I'm not supposed to talk about that. So I guess it'd be the Baltimore Zombie Incident of 2017.

It was my first mission, actually. I don't know why they sent a newbie like me to deal with such a serious case though... it's almost like The Institution was trying to get rid of me >~<

Anyways, there was this huge zombie uprising in Baltimore. It was my job to take out the zombies and infected citizens.

During the mission, I came across a zombie that was different from the others. I called him Mori. Mori had more awareness and humanity than most zombies. I kept him somewhere safe where the other members of the Zombie Control Group wouldn't find him. I visited him every day and fed him whatever I could scavenge from the citizens I had to... dispatch. Mori started getting really attached to me and I started getting attached to him. I guess we were kinda dating? That's what I've always told people.

I couldn't keep him safe forever though... he eventually was found by someone else in the Zombie Control Group and....yeah.

Whoopsies! I didn't mean for that to get so depressing! But yeah, it was a pretty intense mission. It's also what pushed me to start being so pro-anomaly. Anomalies like Mori deserve a chance, ya know? I miss him a lot... but the whole incident happened years ago. I got over him, so hopefully I'll get over what happened to Nadja too someday!

#((thanks for the ask!!!#morilore#allilore#askallianything#tkdb oc#tkdb#tokyo debunker roleplay#tokyo debunker oc roleplay#tkdb oc roleplay

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Black Butterfly: The Harmful Politics of Race and Space in America

The world gasped in April 2015 as Baltimore erupted and Black Lives Matter activists, incensed by Freddie Gray's brutal death in police custody, shut down highways and marched on city streets. In The Black Butterfly―a reference to the fact that Baltimore's majority-Black population spreads out like a butterfly's wings on both sides of the coveted strip of real estate running down the center of the city―Lawrence T. Brown reveals that ongoing historical trauma caused by a combination of policies, practices, systems, and budgets is at the root of uprisings and crises in hypersegregated cities around the country.

Putting Baltimore under a microscope, Brown looks closely at the causes of segregation, many of which exist in current legislation and regulatory policy despite the common belief that overtly racist policies are a thing of the past. Drawing on social science research, policy analysis, and archival materials, Brown reveals the long history of racial segregation's impact on health, from toxic pollution to police brutality. Beginning with an analysis of the current political moment, Brown delves into how Baltimore's history influenced actions in sister cities such as St. Louis and Cleveland, as well as Baltimore's adoption of increasingly oppressive techniques from cities such as Chicago.

But there is reason to hope. Throughout the book, Brown offers a clear five-step plan for activists, nonprofits, and public officials to achieve racial equity. Not content to simply describe and decry urban problems, Brown offers up a wide range of innovative solutions to help heal and restore redlined Black neighborhoods, including municipal reparations. Persuasively arguing that, since urban apartheid was intentionally erected, it can be intentionally dismantled, The Black Butterfly demonstrates that America cannot reflect that Black lives matter until we see how Black neighborhoods matter.

The best-selling look at how American cities can promote racial equity, end redlining, and reverse the damaging health- and wealth-related effects of segregation. Winner of the IPPY Book Award Current Events II by the Independent Publisher

#The Black Butterfly: The Harmful Politics of Race and Space in America#hypersegregated cities#american hate#white supremacy#redlining#Black Neighborhoods#Black communities#racial segregation#violence#american hate and racism

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bibliography

Emily Achtenberg, “Community Organizing and Rebellion: Neighborhood Councils in El Alto, Bolivia,” Progressive Planning, No.172, Summer 2007.

Ackelsberg, Martha A., Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1991.

William M. Adams and David M. Anderson, “Irrigation Before Development: Indigenous and Induced Change in Agricultural Water Management in East Africa,” African Affairs, 1998.

AFL-CIO “Facts About Worker Safety and Health 2007.” www.aflcio.org [viewed January 19, 2008]

Gemma Aguilar, “Els Okupes Fan la Feina que Oblida el Districte,” Avui, Saturday, December 15, 2007.

Michael Albert, Parecon: Life After Capitalism, New York: Verso, 2003

Michael Albert, “Argentine Self Management,” ZNet, November 3, 2005.

Anyonymous, “Longo Maï,” Buiten de Orde, Summer 2008.

Anonymous, “Pirate Utopias,” Do or Die, No. 8, 1999.

Anonymous, “The ‘Oka Crisis’ ” Decentralized publication and distribution, no date or other publishing information included.

Anonymous, “You Cannot Kill Us, We Are Already Dead.” Algeria’s Ongoing Popular Uprising, St. Louis: One Thousand Emotions, 2006.

Stephen Arthur, “‘Where License Reigns With All Impunity:’ An Anarchist Study of the Rotinonshón:ni Polity,” Northeastern Anarchist, No.12, Winter 2007. nefac.net

Paul Avrich, The Russian Anarchists, Oakland: AK Press, 2005.

Paul Avrich, The Modern School Movement: Anarchism and Education in the United States, Oakland: AK Press, 2005.

Roland H. Bainton, “Thomas Müntzer, Revolutionary Firebrand of the Reformation.” The Sixteenth Century Journal 13.2 (1982): 3–16

Jan Martin Bang, Ecovillages: A Practical Guide to Sustainable Communities. Edinburgh: Floris Books, 2005.

Harold Barclay, People Without Government: An Anthropology of Anarchy, London: Kahn and Averill, 1982.

David Barstow, “U.S. Rarely Seeks Charges for Deaths in Workplace,” New York Times, December 22, 2003.

Eliezer Ben-Rafael, Crisis and Transformation: The Kibbutz at Century’s End, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1997.

Jamie Bissonette, When the Prisoners Ran Walpole: A True Story in the Movement for Prison Abolition, Cambridge: South End Press, 2008.

Christopher Boehm, “Egalitarian Behavior and Reverse Dominance Hierarchy,” Current Anthropology, Vol. 34, No. 3, June 1993.

Dmitri M. Bondarenko and Andrey V. Korotayev, Civilizational Models of Politogenesis, Moscow: Russian Academy of Sciences, 2000.

Franz Borkenau, The Spanish Cockpit, London: Faber and Faber, 1937.

Thomas A. Brady, Jr. & H.C. Erik Midelfort, The Revolution of 1525: The German Peasants’ War From a New Perspective. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981.

Jeremy Brecher, Strike! Revised Edition. Boston: South End Press, 1997.

Stuart Christie, We, the Anarchists! A study of the Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI) 1927–1937, Hastings, UK: The Meltzer Press, 2000.

CIPO-RFM website, “Our Story,” www.nodo50.org [viewed November 6, 2006]

Eddie Conlon, The Spanish Civil War: Anarchism in Action, Workers’ Solidarity Movement of Ireland, 2nd edition, 1993.

CrimethInc., “The Really Really Free Market: Instituting the Gift Economy,” Rolling Thunder, No. 4, Spring 2007.

The Curious George Brigade, Anarchy In the Age of Dinosaurs, CrimethInc. 2003.

Diana Denham and C.A.S.A. Collective (eds.), Teaching Rebellion: Stories from the Grassroots Mobilization in Oaxaca, Oakland: PM Press, 2008.

Robert K. Dentan, The Semai: A Nonviolent People of Malaya. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1979.

Jared Diamond, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, New York, Viking, 2005.

Dissent! Network “The VAAAG: A Collective Experience of Self-Organization,” www.daysofdissent.org.uk [viewed January 26, 2007]

Sam Dolgoff, The Anarchist Collectives, New York: Free Life Editions, 1974.

George R. Edison, MD, “The Drug Laws: Are They Effective and Safe?” The Journal of the American Medial Association. Vol. 239 No.24, June 16, 1978.

Martyn Everett, War and Revolution: The Hungarian Anarchist Movement in World War I and the Budapest Commune (1919), London: Kate Sharpley Library, 2006.

Patrick Fleuret, “The Social Organization of Water Control in the Taita Hills, Kenya,” American Ethnologist, Vol. 12, 1985.

Heather C. Flores, Food Not Lawns: How To Turn Your Yard Into A Garden And Your Neighborhood Into A Community, Chelsea Green, 2006.

The Freecycle Network, “About Freecycle,” www.freecycle.org [viewed January 19 2008].

Peter Gelderloos, Consensus: A New Handbook for Grassroots Social, Political, and Environmental Groups, Tucson: See Sharp Press, 2006.

Peter Gelderloos and Patrick Lincoln, World Behind Bars: The Expansion of the American Prison Sell, Harrisonburg, Virginia: Signalfire Press, 2005.

Malcolm Gladwell, The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference. New York: Little, Brown, and Company, 2002.

Amy Goodman, “Louisiana Official: Federal Gov’t Abandoned New Orleans,” Democracy Now!, September 7, 2005.

Amy Goodman, “Lakota Indians Declare Sovereignty from US Government,” Democracy Now!, December 26, 2007.

Natasha Gordon and Paul Chatterton, Taking Back Control: A Journey through Argentina’s Popular Uprising, Leeds (UK): University of Leeds, 2004.

Uri Gordon, Anarchy Alive! Anti-authoritarian Politics from Practice to Theory, London: Pluto Press, 2008.

David Graeber, Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology, Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2004.

David Graeber, “The Shock of Victory,” Rolling Thunder no. 5, Spring 2008.

Evan Henshaw-Plath, “The People’s Assemblies in Argentina,” ZNet, March 8, 2002.

Neille Ilel, “A Healthy Dose of Anarchy: After Katrina, nontraditional, decentralized relief steps in where big government and big charity failed,” Reason Magazine, December 2006.

Inter-Press Service, “Cuba: Rise of Urban Agriculture,” February 13, 2005.

Interview with Marcello, “Criticisms of the MST,” February 17, 2009, Barcelona.

Derrick Jensen, A Language Older Than Words, White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing Company, 2000.

John Jordan and Jennifer Whitney, Que Se Vayan Todos: Argentina’s Popular Rebellion, Montreal: Kersplebedeb, 2003.

Michael J. Jordan, “Sex Charges haunt UN forces,” Christian Science Monitor, November 26, 2004.

George Katsiaficas, The Subversion of Politics: European Autonomous Social Movements and the Decolonization of Everyday Life. Oakland: AK Press, 2006.

George Katsiaficas, “Comparing the Paris Commune and the Kwangju Uprising,” www.eroseffect.com [viewed May 8, 2008]

Lawrence H. Keeley, War Before Civilization. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Roger M. Keesing, Andrew J. Strathern, Cultural Anthropology: A Contemporary Perspective, 3rd Edition, New York: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1998.

Graham Kemp and Douglas P. Fry (eds.), Keeping the Peace: Conflict Resolution and Peaceful Societies around the World, New York: Routledge, 2004.

Elli King, ed., Listen: The Story of the People at Taku Wakan Tipi and the Reroute of Highway 55, or, The Minnehaha Free State, Tucson, AZ: Feral Press, 1996.

Aaron Kinney, “Hurricane Horror Stories,” Salon.com October 24, 2005.

Peter Kropotkin, Fields, Factories and Workshops Tomorrow, London: Freedom Press, 1974.

Wolfi Landstreicher, “Autonomous Self-Organization and Anarchist Intervention,” Anarchy: a Journal of Desire Armed. No. 58 (Fall/Winter 2004–5), p. 56

Gaston Leval, Collectives in the Spanish Revolution, London: Freedom Press, 1975 (translated from the French by Vernon Richards).

A.W. MacLeod, Recidivism: a Deficiency Disease, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1965.

Alan MacSimoin, “The Korean Anarchist Movement,” a talk in Dublin, September 1991.

Sam Mbah and I.E. Igariway, African Anarchism: The History of a Movement, Tucson: See Sharp Press, 1997.

The Middle East Media Research Institute, “Algerian Berber Dissidents Promote Programs for Secularism and Democracy in Algeria,” Special Dispatch Series No. 1308, October 6, 2006, memri.org

George Mikes, The Hungarian Revolution, London: Andre Deutsch, 1957.

Cahal Milmo, “On the Barricades: Trouble in a Hippie Paradise,” The Independent, May 31, 2007.

Bonnie Anna Nardi, “Modes of Explanation in Anthropological Population Theory: Biological Determinism vs. Self-Regulation in Studies of Population Growth in Third World Countries,” American Anthropologist, vol. 83, 1981.

Nathaniel C. Nash, “Oil Companies Face Boycott Over Sinking of Rig,” The New York Times, June 17, 1995.

Oscar Olivera, Cochabamba! Water Rebellion in Bolivia, Cambridge: South End Press, 2004.

George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia, London: Martin Secker & Warburg Ltd., 1938.

Oxfam America, “Havana’s Green Revelation,” www.oxfamamerica.org [viewed December 5, 2005]

Philly’s Pissed, www.phillyspissed.net [viewed May 20, 2008]

Daryl M. Plunk, “South Korea’s Kwangju Incident Revisited,” The Heritage Foundation, No. 35, September 16, 1985.

Rappaport, R.A. (1968), Pigs for the Ancestors: Ritual in the Ecology of a New Guinea People. New Haven: Yale University Press.

RARA, Revolutionaire Anti-Racistische Actie Communiqués van 1990–1993. Gent: 2004.

Revolutionary Association of Women of Afghanistan “About RAWA,” www.rawa.org Viewed June 22, 2007

James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

James C. Scott, “Civilizations Can’t Climb Hills: A Political History of Statelessness in Southeast Asia,” lecture at Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, February 2, 2005.

Jaime Semprun, Apología por la Insurrección Argelina, Bilbao: Muturreko Burutazioak, 2002 (translated from French to Spanish by Javier Rodriguez Hidalgo).

Nirmal Sengupta, Managing Common Property: Irrigation in India and The Philippines, New Delhi: Sage, 1991.

Carmen Sirianni, “Workers Control in the Era of World War I: A Comparative Analysis of the European Experience,” Theory and Society, Vol. 9, 1980.

Alexandre Skirda, Nestor Makhno, Anarchy’s Cossack: The Struggle for Free Soviets in the Ukraine 1917–1921, London: AK Press, 2005.

Eric Alden Smith, Mark Wishnie, “Conservation and Subsistence in Small-Scale Societies,” Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol. 29, 2000, pp. 493–524.

“Solidarity with the Communities of CIPO-RFM in Oaxaca,” Presentation at the Montreal Anarchist Bookfair, Montreal, May 21, 2006.

Georges Sossenko, “Return to the Spanish Civil War,” Presentation at the Montreal Anarchist Bookfair, Montreal, May 21, 2006.

Jac Smit, Annu Ratta and Joe Nasr, Urban Agriculture: Food, Jobs and Sustainable Cities, UNDP, Habitat II Series, 1996.

Melford E. Spiro, Kibbutz: Venture in Utopia, New York: Schocken Books, 1963.

“The Stonehenge Free Festivals, 1972–1985.” www.ukrockfestivals.com [viewed May 8, 2008].

Dennis Sullivan and Larry Tifft, Restorative Justice: Healing the Foundations of Our Everyday Lives, Monsey, NY: Willow Tree Press, 2001.

Joy Thacker, Whiteway Colony: The Social History of a Tolstoyan Community, Whiteway, 1993.

Colin Turnbull, The Mbuti Pygmies: Change and Adaptation. Philadelphia: Harcourt Brace College Publishers, 1983.

Marcele Valente, “The Rise and Fall of the Great Bartering Network in Argentina.” Inter-Press Service, November 6, 2002.

Judith Van Allen “‘Sitting On a Man’: Colonialism and the Lost Political Institutions of Igbo Women.” Canadian Journal of African Studies. Vol. ii, 1972. 211–219.

Johan M.G. van der Dennen, “Ritualized ‘Primitive’ Warfare and Rituals in War: Phenocopy, Homology, or...?” rechten.eldoc.ub.rug.nl

H. Van Der Linden, “Een nieuwe overheidsinstelling: het waterschap circa 1100–1400” in D.P. Blok, Algemene Geschiednis der Nederlanden, deel III. Haarlem: Fibula van Dishoeck, 1982, pp. 60–76

Wikipedia, “Asamblea Popular de los Pueblos de Oaxaca,” en.wikipedia.org /wiki/APPO [viewed November 6, 2006]

Wikipedia, “The Freecycle Network,” en.wikipedia.org [viewed January 19, 2008]

Wikipedia, “Gwangju massacre,” en.wikipedia.org [viewed November 3, 2006]

Wikipedia, “The Iroquois League,” en.wikipedia.org [viewed June 22, 2007]

William Foote Whyte and Kathleen King Whyte, Making Mondragon: The Growth and Dynamics of the Worker Cooperative Complex, Ithaca, New York: ILR Press, 1988.

Kristian Williams, Our Enemies in Blue. Brooklyn: Soft Skull Press, 2004.

Peter Lamborn Wilson, Pirate Utopias, Brooklyn: Autonomedia, 2003.

Daria Zelenova, “Anti-Eviction Struggle of the Squatters Communities in Contemporary South Africa,” paper presented at the conference “Hierarchy and Power in the History of Civilizations,” at the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, June 2009.

Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States. New York: Perrenial Classics Edition, 1999.

#recommended reading#reading list#book list#book recs#organization#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#anarchy#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#acab

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Racism was a long time ago, get over it!" For one, if you think pervasive and systemic racism, both anti-Black as well as racism against other marginalized racial and ethnic groups, in America is "over", you're probably too willfully obtuse to bother to continue reading, but on the rare chance you do, I'll indulge your claim that "racism is over!":

I just turned thirty this month, May twenty twenty-three. My father was born four years before Loving v. Virginia granted the basic right for Black and white peoples to marry each other in every state. My mother was born the same year the Green Book ceased publication. My grandmother was barely thirty when she attended the RFK rally in Indianapolis where Kennedy announced that Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. My father (not in attendance) was not quite five. My father was a fourth grader the year Fred Hampton was assassinated in his own bed by the FBI and local law enforcement. My mother was two years from giving birth to my older brother when the Black Panther Party was torn apart by COINTELPRO, my father was a few couple years into college. My father wasn't even thirty when I was born. My mother is a few years younger.

The LAPD beating of Rodney King and the consequential riots happened almost exactly a year before I was born, I was nineteen when Rodney King passed away. That was two years before Mike Brown was killed by Ferguson police and the consequential uprising. I was twenty-two and living just outside Baltimore the year Freddie Gray was killed in the back of Baltimore PD van from a "rough ride" and the consequential uprising. I had fun (despite covid and the lockdowns) on my twenty-seventh birthday when my four roommates and I got drunk and sung bad karaoke, less than three weeks before George Floyd was murdered (as defined the court and the rulings proving guilt) by Minneapolis PD and the consequential worldwide uprisings. Today I'm just two weeks and a day past my thirtieth birthday when I woke up to the news that a U-haul truck bearing the Nazi flag tried ramming the fence to the White House. That's the same day the NAACP issued a travel warning for Black people to not go to Florida, fifty-seven years after the Green Book ceased publication. This is just a few weeks after Jordan Neely, a Black man my age who was having a mental health episode was killed by a white marine being encouraged by other people in the subway car. Florida governor Ron DeSantis is funding that white marine's defense team.

Ruby Bridges is still alive, as are all but one of the Little Rock Nine–as is the white teenager who was forever caught on camera screaming at them. It's only in the last few years that the civil rights leaders of the Fifties and Sixties who weren't assassinated have started dying of old age, and many more are still alive. I was in seventh grade when Rosa Parks died, I was almost done with third grade when the white bus driver who had her arrested died.

This isn't "a long time ago". This isn't old history. It's all within living memory. Our living memory. Our grandparents' memories, our parents' memories, the memories of you and I that are still forming.

Anyway I don't know how to end this, I'm shaken by the NAACP warning I guess, and I'm not even Black. And you're a willful fool if you think racism is over and has been over for a long time.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

No Justice, No Peace by Devin Allen | Hachette Book Group

About the Author

DEVIN ALLEN is a self-taught artist, born and raised in West Baltimore. He gained national attention when his photograph of the Baltimore Uprising was published on the cover of Time magazine in May 2015—only the third time the work of an amateur photographer had been featured. He is winner of the 2017 Gordon Parks Foundation Fellowship. Also in 2017, he was nominated for an NAACP Image Award as a debut author for his book A Beautiful Ghetto. His photographs have been published in New York Magazine, the New York Times, the Washington Post, and Aperture, and are also in the permanent collections of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC, the Reginald F. Lewis Museum in Baltimore, and the Studio Museum in Harlem. He is the founder of Through Their Eyes, a youth photography educational program, and recipient of an award from the Maryland Commission on African American History and Culture for dynamic leadership in the arts and activism. He lives in Baltimore.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

LIVESTREAM and ALMOST: TODD MARCUS/VIRGINIA MacDONALD with Bruce Barth, Blake Meister, and Eric Kennedy, SMALL’S JAZZ CLUB, 23 JULY 2024, 7:30 and (partial) 9 pm sets

What a find!

Billed as a two clarinet front line with Bruce Barth (sold!), I was ready to watch the later set during the day (and I did). But I came in the middle of the early set in real time just to get a feel for the set and I stayed. TODD MARCUS, it turns out, plays bass clarinet and, remarkably, is an Egyptian American. I came in the middle of the first movement of his Suite Something which was dedicated to the 2011 uprising that was central to that Arab Spring. Clarinets of course suit such music, so I was hooked.

MARCUS is from Baltimore and seems to play regularly with Blake Meister and Eric Kennedy, so they are a solid, tried and true rhythm section. Kennedy can be too exuberant but he has a rich and bright style. Barth is always good to see and he provided a steadiness and heft. VIRGINIA MacDONALD is a more recent collaborator and she really is the co-leader contributing tunes (and organizational chops for this bands recent tour of Canada, where she’s from, and the Northeast) and her own approach to the clarinet. Another thoroughly modern player on the instrument to join Anat Cohen and Ben Goldberg, she wasn’t always as woody as them, sidling up to soprano sax territory while not crossing the line. She was fluid and inventive and wove around Marcus as he wove around her. Her contrafact on George Shearing’s Conception, Retrogression, made that complex tune even trickier and Up High, Down Low was a catchy closer to the second set.

Marcus had another Middle Eastern tune, Cairo Street Ride, that seemed to be the gem of the first set. But, damn, if the following ballad had a commanding quiet with Barth playing an important role. That was probably MacDonald’s; the closer, Windmills, was Marcus’ and it was both easy and pensive.

These folks create compelling music in those paradoxes. I hope to see more of them.

0 notes

Text

Baltimore Uprising after killing of Freddie Gray 2015, Devin Allen photo

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Holidays 4.19

Holidays

Americas’ Day (Honduras)

Army Day (Brazil)

Bicycle Day

Bitcoin Halving Day

Blue Jay Day

Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Action Day

Day of the Indian (Venezuela)

Dog Parent Appreciation Day

Dutch-American Friendship Day

Electrical Load Shedding Day (Ecuador)

419 Day

Global Day of Action Against Spyware

Hanging Out Day

Holocaust Remembrance Day (Poland)

Horseless Carriage Day

Humorous Day

Indian Day (Brazil)

International Day of Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Awareness

International Spandex Day

John Parker Day

King Mswati III Day (Eswatini)

Landing of the 33 Patriots Day (Uruguay)

Leucothea Asteroid Day

Lexington & Concord Day

Lydia Asteroid Day

National Canadian Film Day (Canada)

National Cat Lady Day

National Day of Silence

National Dog Parent Appreciation Day

National Fingering Day

National Hanging Out Day

National Hayden Day

National Health Day (Kiribati)

National Indigenous People’s Day (Brazil)

National North Dakota Day

National Oklahoma City Bombing Commemoration Day

National Paw Parent Appreciation Day

National Poker Day

National Slow Down Day (Ireland)

National Spice Smoking Day

Night of Destiny (Bangladesh)

Navpad Oli (a.k.a. Ayambil Oli; Jain)

Oklahoma City Bombing Commemoration Day

Patriots’ Day (Florida)

Plastic Free Lunch Day

Primrose Day (UK)

Printing Industry Day (Russia)

Refresh Your Goals Day

Republic Day (Sierra Leone)

The Simpsons Day

Snakes Return to Ireland Day

Snowdrop Day

Stoner’s Eve (Orthodox Christian) [Day before 4.20] (a.k.a. ...

4/20 Eve

Got a Minute Day

Gotta Day

The Pre-Bake

Ursine Garlic Day

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising Remembrance Day

World Day of Action in Solidarity with Venezuela

World IBS Day

World Liver Day

Food & Drink Celebrations

Garlic Day

Espresso Italiano Day (Italy)

National Amaretto Day

National Chicken Parmesan Day

National Rice Ball Day

3rd Friday in April

Empire Day (Canada) [Weekday before 24th]

Friendship Friday [3rd Friday]

Fry Day (Pastafarian; Fritism) [Every Friday]

Make a Quilt Day [3rd Friday]

National Clean Out Your Medicine Cabinet Day [3rd Friday]

Weekly Holidays beginning April 19 (3rd Week)

Four-Twenty Weekend (Weekend Closest to 4.20]

National Dance Week [thru 4.28]

Independence & Related Days

Independence Declaration Day (Venezuela)

Kuban (Adoption into Russia; 2018)

Lexmark (Declared; 2019) [unrecognized]

Taman (Adoption into Russia; 2018)

Zimbabwe (Independence Day Holiday)

New Year’s Days

New Years Holidays (Myanmar0

Festivals Beginning April 19, 2024

Baltimore Old Time Music Festival (Baltimore, Maryland) [thru 4.20]

Buds-A-Palooza (Phoenix, Arizona)

California Poppy Festival (Lancaster, California) [thru 4.21]

California Wine Festival (Dana Point, California) [thru 4.20]

Cider, Wine & Done Weekend (Henderson, North Carolina) [thru 4.21]

Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival (India, California) [thru 4.21]

Crawfish Music Festival (Biloxi, Mississippi) [thru 4.21]

Dubai Food Festival Dubai, UAE) [thru 5.12]

East European Comic Con (Bucharest, Romania) [thru 4.21]

Jersey Shore Restaurant Week (Jersey Shore, New Jersey) [thru 4.28]

Kaunas Jazz (Kaunas, Lithuania) [thru 4.29]

La Fete Du Monde (Raceland, Louisiana) [thru 4.21]

Moscow International Film Festival (Moscow, Russia) [thru 4.26]

National Cannabis Festival (Washington, DC) [thru 4.20]

New England Folk Festival (Marlborough, Massachusetts) [thru 4.21]

Northwest Cherry Festival (The Dalles, Oregon) [thru 4.21]

Pompano Beach Seafood Festival (Pompano Beach, Florida) [thru 4.21]

River Falls Bluegrass, Bourbon & Brews Festival (River Falls, Wisconsin) [thru 4.21]

Schmeckfest (South Dakota) [3rd & 4th Fridays]

Texas SandFest (Port Aransas, Texas) [thru 4.21]

Hebrew Calendar Holidays [Begins at Sundown Day Before]

Education and Sharing Day [11 Nisan]

International Passover Joke Day [11 Nisan]

Feast Days

Ælfheah of Canterbury (Anglican, Catholic; Saint)

Alphege (Christian; Saint)

Amanda Sage (Artology)

Bandage and Lozenge-Sucking Competition (Shamanism)

Bendideia (Ancient Greece)

Cerealia (Roman Festival to Ceres, Goddess of Barley & Agriculture)

Conrad of Ascoli (Christian; Saint)

David Koresh Day (Church of the SubGenius; Saint)

Elphege, Archbishop of Canterbury (Christian; Saint)

Emma of Lesum (Christian; Saint)

Expeditus of Melintine (Christian; Saint) [Hoodoo; Nerds; Santerians]

Fernando Botero (Artology)

George of Antioch (Christian; Saint)

Geroldus (Christian; Saint)

Lager Day (Pastafarian)

Leo IX, Pope (Christian; Saint)

Ma Zu (Goddess of the Sea's Birthday; Taoism)

Olaus and Laurentius Petri (Lutheran; Saint)

Persephone’s Return (Pagan)

Pierre (Muppetism)

Strabo (Positivist; Saint)

Start of Pastover (Pastafarian)

Ursmar (Christian; Saint)

Veronese (Artology)

Willem Drost (Artology)

Zoot’s Day (Muppetism)

Lucky & Unlucky Days

Prime Number Day: 109 [29 of 72]

Sensho (先勝 Japan) [Good luck in the morning, bad luck in the afternoon.]

Tycho Brahe Unlucky Day (Scandinavia) [19 of 37]

Umu Limnu (Evil Day; Babylonian Calendar; 18 of 60)

Premieres

Alvin’s Solo Flight (Noveltoons Cartoon; 1961)

Bob & Doug (Animated TV Series; 2009)

Cake Boss (TV Series; 2009)

Carousel (Broadway Musical; 1945)

Fast Color (Film; 2019)

Goodie the Gremlin (Noveltoons Cartoon; 1961)

The Harder They Come, by T. Coraghessan Boyle (Novel; 2015)

Hound About That (Noveltoons Cartoon; 1961)

Illmatic, by Las (Album; 1994)

Iphigenia in Aulis, by C.W. Glucks (Opera; 1774)

Just a Little Bull (Terrytoons Cartoon; 1940)

King of Jazz (Oswald the Lucky Rabbit Cartoon; 1930)

The Land of Fun (Color Rhapsody Cartoon; 1941)

The Last Battle, by Cornelius Ryan (Novel; 1966)

L.A. Woman, by The Doors (Album; 1971)

Mambo No. 5 (A Little Bit of …), by Lou Bega (Song; 1999)

Man for Himself: An Inquiry Into the Psychology of Ethics, by Erich Fromm (Philosophy Book; 1947)

Man Plus, by Frederik Pohl (Novel; 1976)

The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare (Film; 2024)

Money Doodles (Noveltoons Cartoon; 1960)

Moosylvania Saved, Part 1 (Rocky & Bullwinkle Cartoon, S6, Ep. 363; 1965)

Moosylvania Saved, Part 2 (Rocky & Bullwinkle Cartoon, S6, Ep. 364; 1965)

Mrs. Winterbourne (Film; 1996)

My Big Fat Greek Wedding (Film; 2002)

National Barn Dance (Radio Music Series; 1924)

Oblivion (Film; 2013)

Oxford English Dictionary, 1st Edition (Dictionary; 1928)

Peg Leg Pete, the Pirate (Terrytoons Cartoon; 1935)

Plenty Below Zero (Color Rhapsody Cartoon; 1943)

The Producers (Broadway Musical; 2001)

Ring of Fire, by Johnny Cash (Song; 1963)

The Scorpion King (Film; 2002)

The Secret Life of Plants: A Fascinating Account of the Physical, Emotional and Spiritual Relations Between Plants and Man, by Peter Tompkins (Science Book; 1973)

Service with a Guile (Fleischer/Famous Popeye Cartoon; 1946)

Sing, Sing Prison (Terrytoons Cartoon; 1931)

Sinkin’ in the Bathtub, featuring Bosko (Looney Tunes Cartoon; 1930) [1st Warner Bros. cartoon]

A Small Town in Germany, by John le Carre (Novel; 1969)

Stand Up & Cheer (Film; 1934) [1st Shirley Temple film]

Symphony No. 6, by Jean Sibelius (Symphony; 1923)

Ticket to Ride, by The Beatles (Song; 1965)

Timid Tabby (Tom & Jerry Cartoon; 1957)

Tortured Poets Department, by Taylor Swift (Album; 2024)

The Trip (Noveltoons Cartoon; 1967)

Triplet Trouble (Tom & Jerry Cartoon; 1952)

Water, Water Every Hare (WB LT Cartoon; 1952)

Wings (TV Series; 1990)

The Zürau Aphorisms Franz Kafka

Today’s Name Days

Gerold, Leo, Marcel (Austria)

Ema, Konrad, Rastislav (Croatia)

Rostislav (Czech Republic)

Daniel (Denmark)

Aalike, Aleksandra, Alli, Allo, Andra, Sandra (Estonia)

Pälvi, Pilvi (Finland)

Emma (France)

Emma, Gerold, Leo, Timo (Germany)

Haroula, Theoharis, Theoharoula (Greece)

Emma (Hungary)

Emma, Ermogene, Espedito (Italy)

Fanija, Liba, Vēsma (Latvia)

Aistė, Eirimas, Leonas, Leontina, Simonas (Lithuania)

Arnfinn, Arnstein (Norway)

Adolf, Adolfa, Adolfina, Alf, Cieszyrad, Czech, Czechasz, Czechoń, Czesław, Leon, Leontyna, Pafnucy, Tymon, Werner, Włodzimierz (Poland)

Ioan (Romania)

Jela (Slovakia)

Expedito, León (Spain)

Ola, Olaus (Sweden)

Garey, Garett, Garret, Garrett, Garvey, Garvin, Gary, Gerald, Geraldine, Geri, Gerry, Jared, Jarod, Jarred, Jarrett, Jarrod, Jerald,Jeri, Jerod, Jerri, Jerrod, Jerry (USA)

Today is Also…

Day of Year: Day 110 of 2024; 256 days remaining in the year

ISO: Day 5 of week 16 of 2024

Celtic Tree Calendar: Saille (Willow) [Day 6 of 28]

Chinese: Month 3 (Wu-Chen), Day 11 (Guy-Chou)

Chinese Year of the: Dragon 4722 (until January 29, 2025) [Wu-Chen]

Hebrew: 11 Nisan 5784

Islamic: 10 Shawwal 1445

J Cal: 20 Cyan; Sixday [20 of 30]

Julian: 6 April 2024

Moon: 84%: Waxing Gibbous

Positivist: 26 Archimedes (4th Month) [Frontinus]

Runic Half Month: Man (Human Being) [Day 10 of 15]

Season: Spring (Day 32 of 92)

Week: 3rd Week of April

Zodiac: Aries (Day 30 of 31)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Holidays 4.19

Holidays

Americas’ Day (Honduras)

Army Day (Brazil)

Bicycle Day

Bitcoin Halving Day

Blue Jay Day

Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Action Day

Day of the Indian (Venezuela)

Dog Parent Appreciation Day

Dutch-American Friendship Day

Electrical Load Shedding Day (Ecuador)

419 Day

Global Day of Action Against Spyware

Hanging Out Day

Holocaust Remembrance Day (Poland)

Horseless Carriage Day

Humorous Day

Indian Day (Brazil)

International Day of Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Awareness

International Spandex Day

John Parker Day

King Mswati III Day (Eswatini)

Landing of the 33 Patriots Day (Uruguay)

Leucothea Asteroid Day

Lexington & Concord Day

Lydia Asteroid Day

National Canadian Film Day (Canada)

National Cat Lady Day

National Day of Silence

National Dog Parent Appreciation Day

National Fingering Day

National Hanging Out Day

National Hayden Day

National Health Day (Kiribati)

National Indigenous People’s Day (Brazil)

National North Dakota Day

National Oklahoma City Bombing Commemoration Day

National Paw Parent Appreciation Day

National Poker Day

National Slow Down Day (Ireland)

National Spice Smoking Day

Night of Destiny (Bangladesh)

Navpad Oli (a.k.a. Ayambil Oli; Jain)

Oklahoma City Bombing Commemoration Day

Patriots’ Day (Florida)

Plastic Free Lunch Day

Primrose Day (UK)

Printing Industry Day (Russia)

Refresh Your Goals Day

Republic Day (Sierra Leone)

The Simpsons Day

Snakes Return to Ireland Day

Snowdrop Day

Stoner’s Eve (Orthodox Christian) [Day before 4.20] (a.k.a. ...

4/20 Eve

Got a Minute Day

Gotta Day

The Pre-Bake

Ursine Garlic Day

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising Remembrance Day

World Day of Action in Solidarity with Venezuela

World IBS Day

World Liver Day

Food & Drink Celebrations

Garlic Day

Espresso Italiano Day (Italy)

National Amaretto Day

National Chicken Parmesan Day

National Rice Ball Day

3rd Friday in April

Empire Day (Canada) [Weekday before 24th]

Friendship Friday [3rd Friday]

Fry Day (Pastafarian; Fritism) [Every Friday]

Make a Quilt Day [3rd Friday]

National Clean Out Your Medicine Cabinet Day [3rd Friday]

Weekly Holidays beginning April 19 (3rd Week)

Four-Twenty Weekend (Weekend Closest to 4.20]

National Dance Week [thru 4.28]

Independence & Related Days

Independence Declaration Day (Venezuela)

Kuban (Adoption into Russia; 2018)

Lexmark (Declared; 2019) [unrecognized]

Taman (Adoption into Russia; 2018)

Zimbabwe (Independence Day Holiday)

New Year’s Days

New Years Holidays (Myanmar0

Festivals Beginning April 19, 2024

Baltimore Old Time Music Festival (Baltimore, Maryland) [thru 4.20]

Buds-A-Palooza (Phoenix, Arizona)

California Poppy Festival (Lancaster, California) [thru 4.21]

California Wine Festival (Dana Point, California) [thru 4.20]

Cider, Wine & Done Weekend (Henderson, North Carolina) [thru 4.21]

Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival (India, California) [thru 4.21]

Crawfish Music Festival (Biloxi, Mississippi) [thru 4.21]

Dubai Food Festival Dubai, UAE) [thru 5.12]

East European Comic Con (Bucharest, Romania) [thru 4.21]

Jersey Shore Restaurant Week (Jersey Shore, New Jersey) [thru 4.28]

Kaunas Jazz (Kaunas, Lithuania) [thru 4.29]

La Fete Du Monde (Raceland, Louisiana) [thru 4.21]

Moscow International Film Festival (Moscow, Russia) [thru 4.26]

National Cannabis Festival (Washington, DC) [thru 4.20]

New England Folk Festival (Marlborough, Massachusetts) [thru 4.21]

Northwest Cherry Festival (The Dalles, Oregon) [thru 4.21]

Pompano Beach Seafood Festival (Pompano Beach, Florida) [thru 4.21]

River Falls Bluegrass, Bourbon & Brews Festival (River Falls, Wisconsin) [thru 4.21]

Schmeckfest (South Dakota) [3rd & 4th Fridays]

Texas SandFest (Port Aransas, Texas) [thru 4.21]

Hebrew Calendar Holidays [Begins at Sundown Day Before]

Education and Sharing Day [11 Nisan]

International Passover Joke Day [11 Nisan]

Feast Days

Ælfheah of Canterbury (Anglican, Catholic; Saint)

Alphege (Christian; Saint)

Amanda Sage (Artology)

Bandage and Lozenge-Sucking Competition (Shamanism)

Bendideia (Ancient Greece)

Cerealia (Roman Festival to Ceres, Goddess of Barley & Agriculture)

Conrad of Ascoli (Christian; Saint)

David Koresh Day (Church of the SubGenius; Saint)

Elphege, Archbishop of Canterbury (Christian; Saint)

Emma of Lesum (Christian; Saint)

Expeditus of Melintine (Christian; Saint) [Hoodoo; Nerds; Santerians]

Fernando Botero (Artology)

George of Antioch (Christian; Saint)

Geroldus (Christian; Saint)

Lager Day (Pastafarian)

Leo IX, Pope (Christian; Saint)

Ma Zu (Goddess of the Sea's Birthday; Taoism)

Olaus and Laurentius Petri (Lutheran; Saint)

Persephone’s Return (Pagan)

Pierre (Muppetism)

Strabo (Positivist; Saint)

Start of Pastover (Pastafarian)

Ursmar (Christian; Saint)

Veronese (Artology)

Willem Drost (Artology)

Zoot’s Day (Muppetism)

Lucky & Unlucky Days

Prime Number Day: 109 [29 of 72]

Sensho (先勝 Japan) [Good luck in the morning, bad luck in the afternoon.]

Tycho Brahe Unlucky Day (Scandinavia) [19 of 37]

Umu Limnu (Evil Day; Babylonian Calendar; 18 of 60)

Premieres

Alvin’s Solo Flight (Noveltoons Cartoon; 1961)

Bob & Doug (Animated TV Series; 2009)

Cake Boss (TV Series; 2009)

Carousel (Broadway Musical; 1945)

Fast Color (Film; 2019)

Goodie the Gremlin (Noveltoons Cartoon; 1961)

The Harder They Come, by T. Coraghessan Boyle (Novel; 2015)

Hound About That (Noveltoons Cartoon; 1961)

Illmatic, by Las (Album; 1994)

Iphigenia in Aulis, by C.W. Glucks (Opera; 1774)

Just a Little Bull (Terrytoons Cartoon; 1940)

King of Jazz (Oswald the Lucky Rabbit Cartoon; 1930)

The Land of Fun (Color Rhapsody Cartoon; 1941)

The Last Battle, by Cornelius Ryan (Novel; 1966)

L.A. Woman, by The Doors (Album; 1971)

Mambo No. 5 (A Little Bit of …), by Lou Bega (Song; 1999)

Man for Himself: An Inquiry Into the Psychology of Ethics, by Erich Fromm (Philosophy Book; 1947)

Man Plus, by Frederik Pohl (Novel; 1976)

The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare (Film; 2024)

Money Doodles (Noveltoons Cartoon; 1960)

Moosylvania Saved, Part 1 (Rocky & Bullwinkle Cartoon, S6, Ep. 363; 1965)

Moosylvania Saved, Part 2 (Rocky & Bullwinkle Cartoon, S6, Ep. 364; 1965)

Mrs. Winterbourne (Film; 1996)

My Big Fat Greek Wedding (Film; 2002)

National Barn Dance (Radio Music Series; 1924)

Oblivion (Film; 2013)

Oxford English Dictionary, 1st Edition (Dictionary; 1928)

Peg Leg Pete, the Pirate (Terrytoons Cartoon; 1935)

Plenty Below Zero (Color Rhapsody Cartoon; 1943)

The Producers (Broadway Musical; 2001)

Ring of Fire, by Johnny Cash (Song; 1963)

The Scorpion King (Film; 2002)

The Secret Life of Plants: A Fascinating Account of the Physical, Emotional and Spiritual Relations Between Plants and Man, by Peter Tompkins (Science Book; 1973)

Service with a Guile (Fleischer/Famous Popeye Cartoon; 1946)

Sing, Sing Prison (Terrytoons Cartoon; 1931)

Sinkin’ in the Bathtub, featuring Bosko (Looney Tunes Cartoon; 1930) [1st Warner Bros. cartoon]

A Small Town in Germany, by John le Carre (Novel; 1969)

Stand Up & Cheer (Film; 1934) [1st Shirley Temple film]

Symphony No. 6, by Jean Sibelius (Symphony; 1923)

Ticket to Ride, by The Beatles (Song; 1965)

Timid Tabby (Tom & Jerry Cartoon; 1957)

Tortured Poets Department, by Taylor Swift (Album; 2024)

The Trip (Noveltoons Cartoon; 1967)

Triplet Trouble (Tom & Jerry Cartoon; 1952)

Water, Water Every Hare (WB LT Cartoon; 1952)

Wings (TV Series; 1990)

The Zürau Aphorisms Franz Kafka

Today’s Name Days

Gerold, Leo, Marcel (Austria)

Ema, Konrad, Rastislav (Croatia)

Rostislav (Czech Republic)

Daniel (Denmark)

Aalike, Aleksandra, Alli, Allo, Andra, Sandra (Estonia)

Pälvi, Pilvi (Finland)

Emma (France)

Emma, Gerold, Leo, Timo (Germany)

Haroula, Theoharis, Theoharoula (Greece)

Emma (Hungary)

Emma, Ermogene, Espedito (Italy)

Fanija, Liba, Vēsma (Latvia)

Aistė, Eirimas, Leonas, Leontina, Simonas (Lithuania)

Arnfinn, Arnstein (Norway)

Adolf, Adolfa, Adolfina, Alf, Cieszyrad, Czech, Czechasz, Czechoń, Czesław, Leon, Leontyna, Pafnucy, Tymon, Werner, Włodzimierz (Poland)

Ioan (Romania)

Jela (Slovakia)

Expedito, León (Spain)

Ola, Olaus (Sweden)

Garey, Garett, Garret, Garrett, Garvey, Garvin, Gary, Gerald, Geraldine, Geri, Gerry, Jared, Jarod, Jarred, Jarrett, Jarrod, Jerald,Jeri, Jerod, Jerri, Jerrod, Jerry (USA)

Today is Also…

Day of Year: Day 110 of 2024; 256 days remaining in the year

ISO: Day 5 of week 16 of 2024

Celtic Tree Calendar: Saille (Willow) [Day 6 of 28]

Chinese: Month 3 (Wu-Chen), Day 11 (Guy-Chou)

Chinese Year of the: Dragon 4722 (until January 29, 2025) [Wu-Chen]

Hebrew: 11 Nisan 5784

Islamic: 10 Shawwal 1445

J Cal: 20 Cyan; Sixday [20 of 30]

Julian: 6 April 2024

Moon: 84%: Waxing Gibbous

Positivist: 26 Archimedes (4th Month) [Frontinus]

Runic Half Month: Man (Human Being) [Day 10 of 15]

Season: Spring (Day 32 of 92)

Week: 3rd Week of April

Zodiac: Aries (Day 30 of 31)

0 notes

Text

Labor Organizer Spotlight

Herman Grossman, first President of the ILGWU from 1900-1903.

Born in Austria, Grossman later emigrated to New York City and became a cloakmaker. A member of the United Brotherhood of Cloakmakers of New York and Vicinity, he was one of eleven delegates from local unions in New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Newark that, representing roughly 2000 members, founded the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union. At this meeting on June 3, 1900, he was elected the union's first president. During Grossman's first term as president, the International's first local union in Chicago was formed, as well as what would later become one of the ILGWU's most powerful locals, the Amalgamated Ladies' Garment Cutters Union Local 10, was formed.

A portrait of Grossman, c. 1910.

After his second term as union president ended in 1907, Grossman continued to work with the ILGWU. He was a representative of the ILGWU during the "Uprising of the Twenty Thousand" in 1909, and a member of the general strike committee during the "Great Revolt" in 1910. He later worked in the offices of the New York Cloak Joint Board of Cloakmakers Unions.

When Grossman passed away in 1934, David Dubinsky noted that the former ILGWU president, "was not only one of the generals and leaders of the International but also one of its first soldiers who prepared the ground and sowed the seeds from which our Union has sprouted and grown."

#ILGWU#LaborOrganizerSpotlight#Cornell#CornellILR#ILR#Archives#ArchivesOfInstagram#LaborArchives#LaborHistory

0 notes

Text

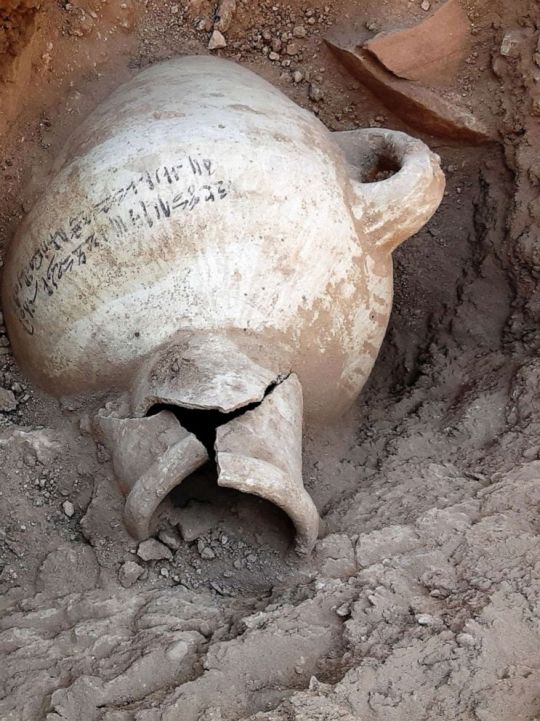

Archeological discoveries are seen in Luxor, Egypt, in this undated handout photo.

Zahi Hawass Center For Egyptology via Reuters

A mission led by Egypt's former antiquities chief Zahi Hawass unearthed "several areas or neighborhoods" of the 3,000-year-old city after seven months of excavation.

MORE: 'Pharaoh's curse' blamed for Suez Canal blockage, other unfortunate events in Egypt

Skeletal human remains sit in the archeological dig site in Luxor, Egypt, in this undated handout photo.

Zahi Hawass Center For Egyptology via Reuters

The city, which Hawass also called "The Rise of Aten," dates back to the era of 18th-dynasty king Amenhotep III, who ruled Egypt from 1391 till 1353 B.C.

"The excavation started in September 2020 and within weeks, to the team's great surprise, formations of mud bricks began to appear in all directions," Egypt's antiquities ministry said in a statement.

"What they unearthed was the site of a large city in a good condition of preservation, with almost complete walls, and with rooms filled with tools of daily life."

The southern part of the city includes a bakery, ovens and storage pottery while the northern part, most of which remain under the sands, comprises administrative and residential districts, the ministry added.

Archeological discoveries sit among the dig in Luxor, Egypt, in this undated handout photo.

Zahi Hawass Center For Egyptology via Reuters

"The city's streets are flanked by houses," with some walls up to 3 meter high, Hawass also said.